Introduction: Meet John A. Watkins. He grew up in Greensboro North Carolina and his family spent summers in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, even during the war. This made John an eye witness to the presence of the German U-Boats. This is his story in his own words. In this podcast, John recounts his father’s service in the Civil Air Patrol, the work of the Coast Guard, and the fear of German invasion.

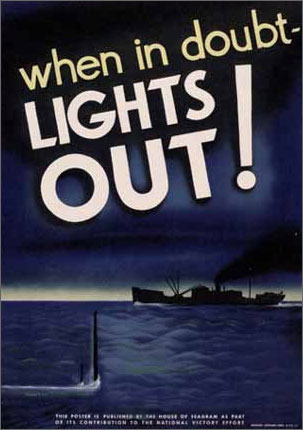

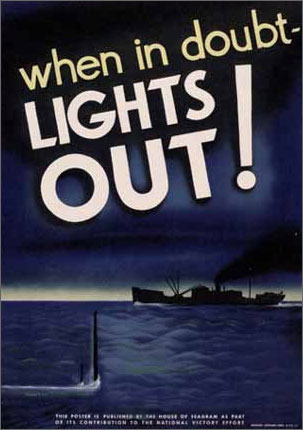

John A. Watkins: The government was very hard-pressed to supply military men overnight, so to speak, and on the coast of North Carolina, there was a great need to have surveillance and whatever action we could take against the opposing submarine forces or what have you. So, they had to press civilian pilots into service, into what was known as the “C.A.P.,” or “Civil Air Patrol,” what was a quasi-military organization that had to do the job until they could get army, navy, marine pilots in place to watch the coast line. And I think they had an airstrip in Skyco, which is over near Wanchese, I may stand corrected on that, but they built a base at Manteo very quickly, and that’s where the C.A.P. base was, and my father was the base commander there. And, eventually, they brought navy planes in there, also. They had to fly everything that would get off the ground and hopefully get back on the ground, which were civilian aircraft, because at the first of the war, there was a great need for every kind of aircraft that we could get our hands on, so they flew every kind of thing that would get in the air. And, as I remember, the maximum thing that most of them could carry, as far as armament, was either one or two 250-pound bombs. They also carried dye markers and smoke, in case they found survivors from torpedoed ships or whatever, but I think one of the main duties was looking for submarines, and another thing that there was always a dire fear of on the Outer Banks was that the submarines would surface at night and put spies ashore in rubber rafts and that type of thing. And, I can vividly remember that there was no light to be shown on the beach at night or after sunset because they didn’t want to do anything, or have anything visible that would aid submarines in navigation or putting spies ashore or whatever. And the Coast Guard used to ride horses up and down the beach with German Shepherd dogs, and if they could see any light coming from a window or whatever, they’d come up and beat on the door and tell you to cut the light out, or whatever. They didn’t want any light showing, and I remember we had to use blackout cloth back then, which, if you were using candles, you had to have this blackout cloth over all the windows where no light would penetrate. I can remember one instance where, one of my main things I liked to do was get up early in the morning and walk the beach to see what I could find that had washed ashore, and one of the biggest disappointments that I had during the war was that one morning I got up very early, and I was walking down the beach, oh, probably about half a mile from our beach home, and I found a pristine, one-man pilot’s rubber raft, a yellow one, floating in the surf, washing up on the beach. And, you might think that I had found King Tut’s treasure. I grabbed the lanyard, and of course it was very light, and I was pulling it back down the beach to our home, and it was quite a thing for me at that time to think that I had found something that had washed up on the beach of some value. But, before I got home, a Coast Guard truck comes along and takes my King Tut’s treasure, and that was the end of that.