Instant Fame

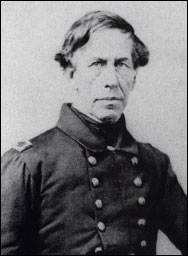

| | Gustavus V. Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy from Aug. 1, 1861 to Nov. 1866. (Courtesy US Navy Historical Center ) |

On the evening of March 9, the news of the battle between the two ironclads had arrived via telegraph in Washington, DC, New York City, and beyond. Gustavus Vasa Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Union Navy, had been one of the many thousands to witness the battle. His first telegram that evening was to Gideon Welles reporting on the events of the day, adding that, though her commanding officer was wounded in the battle, "the Monitor is uninjured and ready at any moment to repel another attack." A second telegram went out a few moments later, from Fox to John Ericsson in New York, letting the inventor know that "your noble boat has performed with perfect success, and Lt. John L. Worden and Chief Engineer Alban C. Stimers have handled her with great skill. She is uninjured."

| | Gideon Welles, 14th US Secretary of the Navy from Mar. 7, 1861 to Mar. 4, 1869. (Courtesy US Navy Historical Center) |

Confederate newspapers naturally told a different story. The Macon Daily Telegraph from Georgia reported on the "perfect success" of the resurrected Merrimac, which "dashed among the Federal craft like a porpoise in a shoal of herrings, scattering, sinking, burning and destroying everything within her reach." The appearance of the Monitor was downplayed, the Union ironclad described as the "curious and formidable nondescript, Erricsson's [sic] floating battery," upon which the Virginia inflicted considerable damage.

Regardless of which side of the conflict a person was on, the public could not get enough information about the vessels and their officers and crew. These men had made history and changed forever the role of a fighting sailor.

| | Samuel Dana Greene. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

Life Goes On

However, following the battle, routine on the vessel carried on as usual. Gustavus Vasa Fox came on board at the dinner hour, expecting to find a disabled vessel and lists of killed and wounded. Instead, he found the officers having a "merry party...enjoying some good beef steak, green peas, &c." Surprised, he exclaimed, "Well, gentlemen, you don't look as though you were just through one of the greatest naval conflicts on record." Samuel Dana Greene answered, half in jest, "No Sir, we haven't done much fighting, merely drilling the men at the guns a little." Other members of the crew joked that one of their number, an "old deaf salt" who was on the berth deck, "innocently asked 'whereabouts the fighting was'" during the battle.

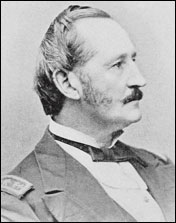

| | Lt. William N. Jeffers had the longest tenure as Captain of the Monitor. (Courtesy US Navy Historical Center) |

After the battle, the Monitor required repairs and a new commanding officer as well. Thus early on the morning of March 10, she repaired to Fortress Monroe and later in the day received Thomas O. Selfridge as her next commanding officer. But his appointment was brief, and he was relieved as soon as Lieutenant William N. Jeffers could arrive to take command of the ironclad. Jeffers served until August 1862, and would have the longest tenure of any commanding officer

on the Monitor.

| | Major General George B. McClellan served during the Civil War. His Peninsula Campaign in 1862 ended in failure. (Courtesy US Navy Historical Center) |

An Ancient China Set

However, even with a new commanding officer, the Monitor did not readily go into battle. Because the Confederates had confounded General George B. McClellan's brilliant Urbanna plan, forcing him to resort to his less brilliant Peninsular plan, McClellan had obviously not been able to neutralize the Virginia before she came out on March 8. But with the Monitor now on hand, McClellan reasoned that this would be easy. Yet neither McClellan nor Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough wished to risk failure. Further complicating matters, President Lincoln himself had ordered that the Monitor not be risked in any fruitless confrontation with the Virginia. Her weaknesses were now known.

| | Paymaster William Keeler was stationed on the Monitor until the ship sank in Dec. of 1862. He wrote many letters to his wife, and these letters have provided a unique look at life aboard an ironclad. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

The Monitor crew chafed under this restriction, and felt as though they were being treated in the same way that "an over careful house wife regards her ancient china set—too valuable to use, too useful to keep as a relic, yet anxious that all shall know what she owns & that she can use it when the occasion demands though she fears much its beauty may be marred or its usefulness impaired." The Virginia seemed to taunt them, as she remained just out of their reach, "smoking, reflecting, & ruminating" each day until sunset when "she slowly crawled off nearly concealed in a huge, murky could of her own emission, black & repulsive as the perjured hearts of her traitorous crew," lamented Paymaster William Keeler.

| | Acting Volunteer Lieutenant William Flye served on the USS Monitor. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

President Lincoln's Visit

President Lincoln was frustrated over the lack of progress in the Peninsula Campaign and was convinced that McClellan himself was to blame. Concerned, Lincoln traveled to Fortress Monroe on May 6, 1862, to personally oversee military operations there. On May 7, Lincoln visited the Monitor. Acting Volunteer Lieutenant William Flye wrote in the Monitor's log that at "1 P.M. President Lincoln & suite came on board." Lincoln, who was keenly interested in new technology and in the vessel he had approved in the fall of 1861, desired to see the Monitor for himself. However, Lincoln did not stay long on his first visit to the Monitor. As he and his party were departing, the cry went up that the "Merrimac was…coming around Sewall's Point apparently bound straight for us." Yet like so many other appearances of the Confederate ironclad, this was yet another tease.

Lincoln ordered Goldsborough to launch his fleet against Norfolk and to open the James River in support of the Peninsula Campaign's advance toward Richmond.

Back into Battle

The weeks of inaction were finally over, and the men of the Monitor prepared their vessel for the bombardment of Sewell's Point with incendiary shells. The newly commissioned USS Galena and two other ships steamed into the James River and began bombarding Fortress Boykin, while the Monitor, joined by the Seminole, Dacotah, Susquehanna, San Jacinto and Naugatuc, began shelling the Sewell's Point Battery.

The attack was of short duration. The Confederate forces within the fortifications were small in number and were unable to return effective fire. The shelling drew the Virginia out of Gosport to challenge the Union assault. Shelling continued throughout the following day, and the Virginia continued to be a menacing, yet distant presence. Still under orders not to engage the Confederate ironclad directly, Jeffers left her alone, to the chagrin of his men. They did not want the Galena or any of the other gunboats to be the vessel that destroyed the Virginia. Let them have the Jamestown, Yorktown, and Teaser, only save the "Big Thing," as the men called the Virginia, for the Monitor. They desired once again to take her on single-handed, "as a crowning glory to our career so finely commenced," wrote Keeler.

| | Benjamin Huger entered West Point in 1821, but with the secession of his home state of South Carolina, he resigned from the Union Army and was commissioned in the regular Confederate Army. He briefly commanded the forces in and around Norfolk, Va. (Courtesy Library of Congress) |

The Destruction of the Virginia

Confederate Army Major General Benjamin Huger asked for the Virginia to position herself at Craney Island to cover the Confederate retreat from Norfolk to Portsmouth. However, on the morning of May 10, 1862, Union forces landed on the shore of the Ocean View section of Norfolk and began moving inland. Huger abruptly abandoned Norfolk.

By 5 p.m., Union troops had reached downtown Norfolk where the Mayor, William Lamb, had staged an elaborate surrender ceremony involving presenting the "keys to the city" to the Union commander, a ruse, which allowed the Confederate army time to leave the town and destroy the Navy Yard. Flames once again engulfed Gosport, this time set by Confederate hands. In the frantic rush, Huger neglected to inform Commander Josiah Tattnall, now in command of the CSS Virginia, that Norfolk had fallen earlier than anticipated.

| | On May 11, 1862, in the face of advancing Union troops, Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall ordered the destruction of his flagship, CSS Virginia. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Historical Center) |

The Virginia was now without a home and Tattnall faced a dilemma. If he attempted to attack the Union fleet, he had some hope of destroying several vessels before being sunk, or worse, captured. He rejected this plan because of the risk. Making a run for the open waters of the Bay was impossible because the only channel deep enough ran directly between the massive guns of Fortress Monroe and the Rip Raps (now Fort Wool). Some officers reportedly suggested that they abandon her to the enemy, wait for the celebration they knew would come, and sink the ram with the carousing Union sailors on board. However, the only viable option was to lighten the vessel's load enough to allow her to pass over the James River bar and thus allow her to steam to Richmond for that city's defense.

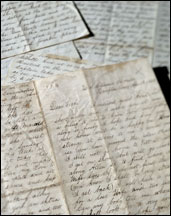

| | George Geer letters. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

With the Virginia crew working well into the night throwing everything they could overboard, they had succeeded in gaining three feet of draft when the wind abruptly changed around midnight. The Virginia's pilots thought that the westerly wind would drive the tide out even more and the vessel could never get past the bar. Only one course of action remained. Just as she had been destroyed to keep her from enemy hands before, now the vessel faced destruction by her own men once again. At 2 a.m. the call was given for the Virginia crew to "splice the main brace" by drinking a double ration of grog. Then Tattnall ordered the vessel run aground at Craney Island and the men told to evacuate. A small detachment rigged the vessel to explode, and set her ablaze.

Early in the morning of May 11, 1862, Fireman George Geer recalled that "a very large Explosion took place and nothing could be seen of the Merimack [sic] after it." The sound brought the entire crew of the Monitor on deck. The Monitor boys had been robbed of their chance to destroy the Confederate ironclad.

The following morning, the Monitor steamed up the Elizabeth River towards Norfolk. On the way, the Monitor crew got their first glimpse of what was left of the Virginia. Several collected souvenirs to send home. Arriving in Portsmouth, they tied up at the Virginia/'s old moorings in Gosport, under the curious and quietly hostile eyes of the locals. Lincoln and his retinue steamed past the Monitor, the President doffing his signature hat to the crew and bowing in thanks for their part in the action. After a brief conference, Goldsborough ordered Jeffers back to Hampton Roads and then up the James River to Richmond the next day.

The Monitor and the Naugatuck began to move up the James River. While fortifications at Day's Bluff in Isle of Wight County lobbed a few shots at the Monitor, no one was harmed. Rendezvousing with the Galena, Aroostook and Port Royal at Jamestown Island, the Monitor and Naugatuck led the fleet further up river. With Confederate sharpshooters hiding along the banks, the Monitor men found themselves confined below deck.

Drewry's Bluff

While the two ironclads would not meet again in battle, their crews would meet once more at Drewry's Bluff. Leaving their burning vessel behind, several of the crew of the Virginia moved west, following the James River to Fort Darling. On May 15, 1862, the Union fleet began its attack on Fort Darling, situated high on Drewry's Bluff.

| | Drewry's Bluff is located in northeastern Chesterfield County, Va. It was the site of the Confederate Fort Darling during the Civil War. This photo was taken in 1865. (Courtesy Library of Congress) |

Captain Jeffers, attempting to aim the guns more effectively, stationed himself behind a barricade of rolled-up hammocks atop the turret for part of the action. Yet there was no possibility of claiming victory for the Monitor in this engagement. She and her consorts could gain no advantage over the fortification up on the bluff. Due to a serious design flaw, the Monitor could not elevate her guns, making the turreted vessels ineffective against such high fortifications.

| | John Taylor Wood graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1853. Due to his sourther sympathies, he resigned his commission in April 1861. In October 1861, he received a commission as a First Lieutenant in the Confederate Army. (Courtesy U.S. Navy Historical Center) |

The ventilation within the turret was inadequate to handle the warm May day. Temperatures within the turret rose to an oppressive 140 degrees and several of the gunners fainted from a combination of the heat and gases from the gunpowder and engine, as well as smoke and heat from lamps and the "emanations" from the sixty men who had been enclosed in the "fetid atmosphere" for hours. The Monitor proved to be "a mighty hot concern in warm weather."

With high casualties and dwindling ammunition, the Union fleet retreated. From the bluff, Lt. John Taylor Wood shouted after the Monitor, "Tell Captain Jeffers that is not the way to Richmond."

| | Chief Engineer Isaac Newton. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

The Long Hot Summer

The late spring and summer of 1862 was a difficult one for the Monitor boys. Unable to return fire effectively against shore batteries, suffering from the heat, bad food and incessant mosquitoes, they found that they spent their time up the James River ultimately more for national morale than for any direct martial purpose. Chief Engineer Isaac Newton quipped to his mother that "if that's the case morale effect must be pretty well strewed along the river in these parts from the number of times we have passed up & down..."

| | Acting Master Louis Stodder. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

By June, the Monitor's log book entries become a litany of temperatures, and both the vessel and the men began to cranky. One June 2, 1862, William Flye noted that "at 5 am got underweigh & proceeded up the river followed by the rest of the fleet. At 8 am anchored in consequence of a derangement of the engine." This fault in the engine meant that the blowers were not functioning properly as a result. On June 12 Flye, standing the afternoon watch wrote, "[A]t 1 pm thermometer stood 142 degrees inside the galley, the door being open and the blowers of the engine being in action." By the next day at noon, Acting Master Louis Stodder was able to report that the "thermometer stood at 165 in the galley." On the 14th the engine was once again deranged and the temperatures soared. The celebrated flushing toilets were heated to a fetid 131 degrees. A cool front brought some relief for the next several days, but at 1:30 a.m. on June 23, Stodder and his watch discovered a fire around the stovepipe of the galley. Though they were able to extinguish it, there was enough damage to take the galley out of commission for several days. During this time, John Ericsson rather uncharacteristically sent a sympathetic note to his friend Isaac Newton saying, "I admit that you have had a very severe trial and cannot imagine anything more monotonous and disagreeable than life on board the Monitor, at anchor in the James River, during the hot season."

To make matters worse on the James, Paymaster Keeler had initially miscalculated the timing of fresh provisions, so they had gone up river at a deficit. Geer complained to his wife about how the Paymaster was new and green and because of his inexperience they were having to use molasses in their coffee. Supplies did arrive, however, and while the men complained about all of the tasty sesesh beef walking around on the banks of the James, they did eventually manage to get fresh food throughout the summer. In fact, Keeler noted that "…a portion of our iron deck has been converted into a stock yard containing just at present, one homesick lamb, one tough combative old ram, a consumptive calf, one fine lean swine, an antediluvian rooster & his mate, an old antiquated setting hen…"

The Forgotten Battle

The fleet attempted to steam up the Appomattox River in late June in an attempt to destroy a railroad bridge at Swift Creek and thus cut off a critical supply route for the Confederates. On the evening of June 26, a spectacular diverting fire was taken up by the Galena and the Port Royal so the small gunboats could achieve their objective. Yet the Appomattox proved too treacherous; The Monitor, together with three gunboats "got in a perfect mess on the bar," recalled Isaac Newton and several vessels ran aground. In addition, many in the small boats detailed to row ahead and set fire to the bridge feared that there might be Confederate sharpshooters along the banks of the river, which had narrowed considerably around the fleet as they steamed further in. The assembled officers of the small fleet determined it was too dangerous to press on, and the fleet, once they had been re-floated, in some cases had to steam backwards out of the narrow river. One small steamer, the Island Belle, could not be refloated and was destroyed.

The mission was a failure, according to Keeler; "Four or five thousand dollars worth of ammunition expended, one Steamer…burned, a large quantity of whiskey drank, with what result? A number of people badly frightened & the corner of a house knocked off…." It was an ignominious chapter in the Monitor's career, yet one that went largely unmentioned.

| | Hunter Davidson resigned his commission as a U.S. Naval officer in April 1861 and received a Confederate Navy commission as First Lieutenant in June. He was an officer on the ironclad Virginia and commanded the CSS Teaser. Here, he is photographed in civilian dress, probably during or soon after the Civil War. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Historical Center) |

A Small Success

There was one small success shortly after the Appomattox raid, however. In the final days before McClellan's retreat, the Monitor and the steamer Maratanza happened upon their old foe the CSS Teaser at Turkey Island in the James River. Commanded by Hunter Davidson, late of the CSS Virginia, the Teaser was transporting Confederate army officers to locations near Chaffin's Bluff on the James. Two shells from the Maratanza disabled the Teaser and all on board leapt into small boats and "skeedadled" ashore, leaving papers and other war material on board. Among the items captured were diagrams of mines laid by the Confederates in the James River near Richmond, and, of particular importance to the men of the Monitor, Hunter Davidson's private memorandum book that outlined a clever attack plan on the Monitor.

First Photographs

Ultimately, the Union did not take Richmond in the spring and summer of 1862. The Monitor had spent her time on the James, first supporting McClellan's advance, and then, with the failure of the Seven Days campaign in early July, his retreat. Her morale effect had not been enough to take Richmond. Yet the public still wanted to know more about her. The Monitor and her men were celebrities. Yet all of the images of the vessel to that point had been hand drawn, painted, or engraved. Therefore, as the Union fleet retreated down the James River, Union photographer James F. Gibson came on board to document the celebrated ironclad and her crew. It was also hoped that Gibson's visit to the ironclad would coincide with President Lincoln's next visit.

| | One of eight known stereoscopic images taken of the USS Monitor by Gibson. The glass plate is missing a portion of the lower left corner. Click here for a larger image. (Courtesy of Library of Congress) |

Both Gibson and Lincoln visited the Monitor on July 9, 1862, as she lay anchored off Berkeley Plantation on the James River. Lincoln arrived at 7:45 a.m., before Captain Jeffers was awake. Lincoln had a boat sent for Goldsborough to attend him on the Monitor. The meeting was apparently brief, and both men left before Jeffers ever made his appearance. Goldsborough had been relieved of command and Captain Charles Wilkes would be taking over as Flag Officer that afternoon.

| | Captain Charles Wilkes. (Courtesy NOAA.) |

Gibson arrived in the afternoon as well and though the President had left, he took eight photographs of the men of the Monitor, the only known photographs of the vessel in existence. Some of the shots seem composed in order to take in the still-visible battle damage on both the hull and the turret while other shots are clearly taken to show the officers and crew. One image of the crew shows a young black man crouched in the foreground, possibly Siah Carter from Shirley Plantation. Next to him, a makeshift galley sits on the weatherdeck, a remnant from the fire on June 23. Another crew shot shows the men more relaxed, some playing checkers while another reads the newspaper, seemingly unaware his portrait is being made. Three photographs show the officers in various combinations, joined by a Lieutenant from the Galena. A final photograph shows Jeffers alone, a visual testament to his alienation from his men. Copies of the photographs were given to the men, some of whom sent them home to their families. The fatigue and frustration lined upon their faces.

| | On August 9, 1862, Commander Thomas Stevens, Jr. was placed in command of the Monitor, replacing Jeffers. He was in command for less than two months, and during his command the Monitor saw almost no action. (Courtesy U.S. Navy Historical Center) |

Changes on the Wind

Other changes were in store for the Monitor. On August 15, Captain Jeffers announced that he would be leaving for a position in which he would supervise the building of more ironclads. On the 18th, he was relieved of command by his replacement, Commander Thomas Holdup Stevens, Jr., late of the Maratanza. Chief Engineer Isaac Newton was detached from the vessel on August 20. Like Jeffers, he would be overseeing the construction of more ironclads.

Drewry's Bluff and another assault on the Appomattox seemed to be a real possibility for the Monitor in late August, and preparations were underway for both. However, on the 28th the fleet received orders to proceed down the James River to Hampton Roads, where on August 30 they anchored, a few yards from the sunken Cumberland. The feeling of freedom of the salt air, and from being targets of Confederate sharpshooters, was obvious.

| | John Pine Bankhead. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

Other changes were afoot as well. Stevens was detached from the Monitor in mid-September, having "won the respect & esteem" of the men. In contrast to his predecessor Jeffers, Stevens had made the vessel "seem like another place, his treatment of his officers & men has been so kind & pleasant." John Pine Bankhead, a career navy man from South Carolina and a cousin to Confederate General John Bankhead Magruder, would be their new commander. With Bankhead's arrival, a new logbook was started. The old logbook was sent to the Navy Department.

The late September days in Hampton Roads would be pleasant ones for the crew of the Monitor. Fresh seafood was plentiful and fresh vegetables and some fruits were still available. The men experimented with hand grenades in anticipation of the new Merrimac's appearance. Despite the relative calm, it was with great relief that the Monitor was finally ordered to the Washington Navy Yard for repairs on September 30, 1862. Her hull was fouled with seven months of marine growth and her engines had been in need of repair since June. Taken under tow by a small tug, the Monitor slowly made her way to Washington.

Washington Navy Yard

The Monitor herself received a warm welcome when she arrived at the Yard, and several curious citizens tried to catch a glimpse of the ironclad from small boats that swarmed the perimeter of the Navy Yard. On Saturday, October 6, before most of the officers and crew could begin their leave, the Monitor was opened to the public.

Keeler wrote that "[t]he docks were lined with carriages—& it was in fact a perfect jam—no caravan or circus ever collected such a crowd…." The men enjoyed the attention. That evening, guards were stationed at the dock in order for the officers and crew to be able to eat their evening meal without the intrusions of the public.

Navy officials tightened security during the repairs, but bowing to public pressure, they placed a small ad in the Washington Daily Intelligencer on Thursday, November 6, 1862, which read: "The 'MONITOR' will be open to the public this (Thursday) afternoon, from one o'clock until sunset. This is the only opportunity the public will have to see her. Passes will not be required at the navy yard gate." Soldiers, sailors, civilian men, women and children all turned out to tour the celebrated ironclad. This time, however, most of the officers and crew were still on leave, not to return until later that night. Seeking souvenirs, the crowds took whatever they could remove, as there was very little security to stop them. Acting Master Louis Stodder recalled "[w]hen we came up to clean that night, there was not a key, doorknob, escutcheon – there wasn't a thing that hadn't been carried away."

Rushing to complete the work on the vessel, workmen at the Navy Yard continued painting and installing woodwork and ironwork (and replacing those items that had been taken by the tourists) while officers and crew began moving ships stores, coal, and their personal possessions back on board.

Back to Newport News, Va.

Finally, on November 9, though "everything was tumbled aboard after a fashion," the Monitor left Washington, D.C. and returned south to her "old moorings off Newport News."

The Monitor's time at the Washington Navy Yard had yielded several changes to the vessel. On their return in early November, the men found that their ship had undergone significant changes. A telescopic smoke pipe some 30 feet in height had been installed and everything gleamed with fresh paint. The berth deck had been raised up significantly to afford storage space underneath, and the storage rooms to either side of the berth deck had been reduced by several feet, leaving far more room for living quarters. More powerful blowers for ventilation had been installed. Iron cranes and davits had been affixed to the weather deck for new ship's boats. New awnings had also been provided to shade both turret and weather deck. She was like a new vessel.

The changes to the vessel were not the only new things on board. There were new officers and crew as well. Some men had been officially detached from the vessel when she arrived in Washington while others sought to detach themselves in less official ways, deserting for better appointments, or through drunken mishaps. In all, twenty men came on board to replace the crew that either had been reassigned or deserted.

New Orders

On Christmas Eve 1862, orders came in for the USS Monitor to proceed to Beaufort, N.C., then presumably to Charleston, S.C., though it was not stated in the orders. On Christmas Day, both officers and crew observed the holiday with both work and festive food and drink. Some of the crew had leave to go ashore and encountered the crew of several British vessels that were in port. The men mingled together "on the best of terms till the parties got too much whiskey when a fight would have to decide who was the best man of the two." William Keeler, who was ashore and witness to the brawl said that by the evening, "there seemed to be a sort of general mass, black eyes, bloody noses, & battered faces seeming to predominate."

The next few days, while the crew waited for the weather to clear, they placed oakum between the turret and its brass deck ring, though they did not seal it with pitch. They bolted and caulked the gun-port shutters, caulked the pilothouse slits, and secured iron covers over the deck lights. George Geer wrote to his wife that he sealed the hatches with "Red Lead putty, and the Port Holes I made Rubber Gaskets one inch thick and in fat had every thing about the ship in the way of an opening water tight." They needed to be cautious, for they were about to enter the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

On December 29, two massive hawsers were passed from the Monitor to the vessel assigned for the ocean tow—the USS Rhode Island. The Monitor's small boats were transferred to the consort vessel where they could be kept safe. At 2:30 p.m. John Bean, a local pilot, came on board the Rhode Island and the two vessels got underway. The weather was clear and pleasant, and John Bankhead wrote that there was "every prospect of its continuation." As the Monitor was leaving Hampton Roads, her former commander, John Worden, was entering the roadstead in another monitor, the USS Montauk. The Monitor and Rhode Island passed Cape Henry at 6 p.m. and thus entered the Atlantic Ocean.

| |

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html