Battle of Hampton Roads

Ordered to Hampton Roads, Va., the USS Monitor arrived on the evening of March 8, 1862. The scene that greeted her crew that evening was horrifying. The prediction that a “single ironclad, in the midst of a hostile wooden fleet, would resemble a lion amid a flock of sheep” had proven correct.

| | Painting of the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia battle in Hampton Roads March 9, 1862. (Courtesy Library of Congress) |

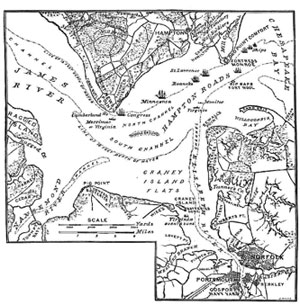

Previously that day, with the shore lined with cheering crowds of spectators and soldiers, CSS Virginia and her escorts had steamed down the Elizabeth River. At anchor near Fort Monroe were the USS Minnesota, USS Roanoke, and USS St. ‘Lawrence along with several gun-boats. Off the shores of Newport News, USS Congress and USS Cumberland were quietly moored, neither aware of the approaching Virginia.

As CSS Virginia made her maiden voyage into Hampton Roads that day, she proved the effectiveness of iron against wood. In less than an hour, the Virginia rammed and sank the Cumberland. The Congress was run aground and unable to effectively to bring her guns to bear on the Virginia. The Congress finally surrendered to end the slaughter. The fires started during the fight soon engulfed the ship in flames, which assured her complete destruction. The Minnesota was also badly damaged and aground.

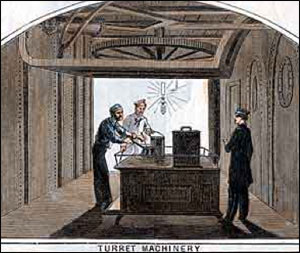

| | Below Monitor's deck under the turret. (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) |

With two men killed and nineteen wounded, the Virginia steamed to Sewell's Point. Her smoke stack was pierced, her boat and anchors were shot away, and she had a leak from where her iron prow had broken away. Although she was a little worse for the wear, her armor had proved impregnable, verifying once and for all the great superiority of iron over wood.

As the Monitor anchored at 9:00 PM, Lt. Worden, Monitor's Captain, was ordered by Captain Marston aboard the Roanoke to defend the Minnesota. The brightly burning Congress lit up the night sky and provided a beacon that guided the Monitor towards the Minnesota. The atmosphere of gloom was overwhelming. Lt. Greene onboard the Monitor wrote:

| | An atmosphere of gloom pervaded the fleet, and the pygmy aspect of the newcomer did not inspire confidence among those who had witnessed the day before…Reaching the Minnesota, hard and fast aground, near midnight, we anchored, and Worden reported to Captain Van Brunt. Between 1 and 2 AM the Congress blew up—not instantaneously, but successively. Her powder-tanks seemed to explode, each shower of sparks rivaling the other in its height, until they appeared to reach the zenith—a grand but mournful sight. Near us, too, at the bottom of the river, lay the Cumberland, within her silent crew of brave men, who had died while fighting their guns to the water’s edge, and whose colors were still flying at the peak.

|

The atmosphere on the Monitor was tense as the crew prepared for battle. No one got any sleep (not that they could have slept if they had wanted to) because the crew discovered that the turret mechanism had rusted from seawater. They spent the night lubricating and reworking the gears so that the turret would operate smoothly. This was not an easy process, as the 120-ton turret had to be jacked up so that the edge would clear the deck. The crew also had to remove the guns and their carriages along with the shot and powder. The Monitor's crew worked through the night, and as the sun rose over Hampton Roads, they were ready to meet their adversary.

| | Currier and Ives print of the fight between the Monitor and the Virginia on March 9, 1862. (Courtesy Library of Congress) |

At about 7:30 AM, on Sunday, March 9, 1862, the Virginia once again steamed out to re-engage the stranded Minnesota. Signals passed between the Union ships at anchor, but before Captain Van Brunt of the Minnesota could send any official instructions to Worden, the Monitor was already underway and steaming out to meet the Virginia. No instructions were necessary. Captain Worden knew what to do and steamed as far as possible away from the Minnesota before engaging in the first battle where iron would meet iron.

For hours, the two armored warships fired upon each other, each side looking for their opponent's weaknesses. At times, the two vessels were touching, but the cannon shots bounced harmlessly off their iron armor. Almost four hours into the battle, a shot from the Virginia exploded against the forward side of the Monitor’s pilothouse, temporarily blinding Worden.

| | Map of Hampton Roads and Vicinity from The Century Magazine, Vol. XXIX, March 1885, Public Domain. Click here for a larger map. |

The Monitor pulled out of action to assess the damage to the ship. Lieutenant Catesby Jones, the Virginia's commander, saw the Monitor leaving the battle. He assumed the Virginia had done serious damage to the Union ironclad and had forced her from the field. After two days of fighting, the Confederate ironclad had expended tons of coal and ammunition and the crew was exhausted. Jones gave the order for the Virginia to return to the navy yard to assess the damages.

The Monitor, now under the command of Lt. Samuel D. Greene, left the shallow bay she had pulled in and steamed back into Hampton Roads. Seeing the Virginia heading towards the Elizabeth River and Norfolk, Greene assumed that the Monitor must have done serious damage to the Virginia and that she was retreating from the fight. As Greene's orders were to protect the Minnesota, he returned to her side until the wooden warship was floated on the next tide.

Although, the Battle of Hampton Roads was ultimately fought to a draw, the true significance of the engagement was that the era of the wooden warship was at an end. From that day forth, iron would forever rule the seas.

| |

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html