Construction Begins

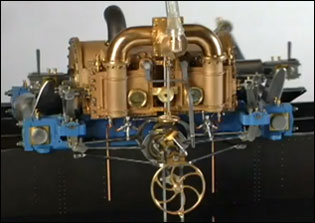

John Ericsson had claimed he could deliver an ironclad in 90 days. Today, even with advanced technology, it would prove difficult to build a ship of that size and structure in such a short time! But Ericsson, having complete confidence in himself and not being very humble, had already been hard at work, even before the contract was signed. Ericsson, confident that nothing would go awry with the negotiations, had begun work on the engine that would power the gunboat. Thus, the vibrating side-lever engine was already taking shape at Delamater's foundry.

| |  | | |

| | Visit YouTube to view a model of the vibrating side-lever engine. | |

Ericsson had created similar engines before and decided to use the design again because of its distinctive advantages on a small, low-riding warship. Most steam engines of the time had pistons that operated in a vertical motion, which occupied a lot of space and made them vulnerable to enemy fire because they were partially above the waterline. In contrast, the Monitor's 30-ton, 400-horsepower engine had pistons that moved horizontally, which reduced the height of the engine and allowed it to be mounted below the waterline.

| |  | | |

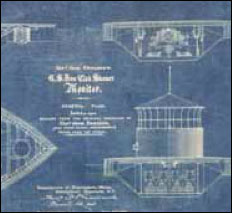

| | Monitor Blue Print, (Courtesy The Mariners' Museum) | |

To further streamline the construction, Ericsson chose to significantly modify his original plans. A conventional pair of Dahlgren smoothbore guns in the turret replaced the steam-powered gun and torpedo he had hoped for. The circular dome soon became a cylindrical turret, and the sloping deck became a nearly flat deck—just as unconventional, but much easier to construct.

Finally, on Oct. 4, 1861, the Navy signed the contract giving Ericsson 100 days to build an ironclad. The contract acknowledged Ericsson's considerable experience with ship design, but also offered the Navy ample opportunity to get out of paying for the ship if Ericsson did not meet the demands of the contract.

| |  | | |

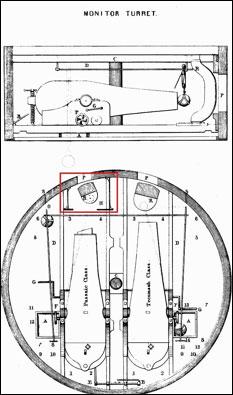

| | Engraving of hypothetical monitor turret showing both XV-inch Short “Passaic" and XV-inch Long “Tecumseh” mounted in same turret. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Historical Center) | |

Working Together

To save time, nine contractors and an unknown number of subcontractors worked simultaneously in at least seven different cities to produce the components for assembly at Continental Ironworks in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. It was an incredibly complex manufacturing process—but then, this would be no ordinary ship. A member of the Monitor's crew, David Roberts Ellis, would later recall, “Thus the war for the moment was being carried on not at Hampton Roads but at Norfolk and Brooklyn, and the victory was to depend, not only upon the bravery of the officers, but upon the speed of the mechanics. It was a race of constructors….”

The strong industrial capabilities of the Union made it possible to even consider building an experimental vessel in 100 days. Ironworks throughout New York State worked to manufacture the raw and finished materials needed to build Ericsson's Battery. Yet New York boasted no foundry capable of rolling the 192 plates needed for the most important feature of the vessel—the rotating gun turret.

The turret was composed of eight layers of one-inch-thick laminated iron. The thickness of the iron was not an issue for the New York companies; rather, the problem was the nine-foot length of each plate. The only foundry within the Union capable of rolling plates up to ten feet in length was in Baltimore, Maryland—Abbott and Sons in the Canton area of the city. Thus, Thomas Rowland of Continental Ironworks, with Charles Whitney acting as his agent, subcontracted with Abbott to make the plates.

| |

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html