Sinking of the Monitor

Just before dawn on December 30, the USS Monitor, in tow of the USS Rhode Island, began to "experience a swell from the southward" and as the day progressed, the clouds increased "till the sun was obscured by their cold grey mantle.” Officers and crew amused themselves by watching three sharks swim alongside the ship. Soon, however, the sea began to break over the vessel, the waves white with foam. As the weather grew worse, the men were forced to go below decks. At 5:00 p.m., the officers sat down to dinner in the wardroom, joking about being free from their "monotonous inactive life."

As the Monitor prepared to round Cape Hatteras, waves hit the turret so hard it trembled. But the crew was elated: "Hurrah for the first iron-clad that ever rounded Cape Hatteras!" they cried. "Hurrah for the little boat that is first in everything!" By 7:30 p.m. one of the hawsers snapped and the Monitor began rolling wildly. The increased motion forced out some of the oakum under the turret and water started pouring in through the gaps.

The situation below deck was serious. The water level had risen to one inch in the engine room, and Captain Bankhead ordered Engineer Joseph Watters to put the Worthington pumps to work. Water had also reached the coalbunkers, and the coal was growing too wet to keep up the steam in the engines. The pressure, which normally ran at 80 pounds, had dropped to 20 pounds—dangerously low. The Captain ordered the large centrifugal pump into action. Mountainous waves crashed over the Monitor's deck as the storm intensified. The pilothouse was almost continuously under water. Many of the men were on top of the turret. Bankhead "signalized several times to the Rhode Island to stop." The engineers reported that the pumps were having no effect.

At 8:45 p.m., the Rhode Island stopped. For a moment, the Monitor seemed to ride more easily. But the wind kept picking up. The waves now began "...burying her completely for an instant, while for a few seconds nothing could be seen of her from the Rhode Island but the upper part of her turret surrounded by foam."

At 10 p.m. the engineers told Bankhead that the water was more than a foot deep in the engine room—so deep that the blowers were spitting water. Surgeon Grenville Weeks wrote, "...the vessel's doom was sealed; for with [the fires'] extinction the pumps must cease, and all hope of keeping the Monitor above water...." The men organized a bucket brigade, but it did no good except to lessen the crew's panic. Weeks recalled, "Some sang as they worked, and... the voices, mingling with the roar of the waters, sounded like a defiance to Ocean."

| |  | | |

| | Illustration by Norm Cubberly showing what possibly happened to the Monitor after she slipped beneath the waves on December 31, 1862. Click here for a larger image. (Monitor Collection, NOAA) | |

At 10 p.m. Bankhead gave the order for the red distress lantern to be hoisted. The engines were slowed to preserve steam for the pumps. But the decrease in speed made the hawser sag, and the ironclad became unmanageable. Bankhead called for volunteers to cut the towline. Master Louis Stodder, Boatswain's Mate John Stocking, and Quarter Gunner James Fenwick climbed down the turret, but eyewitnesses said that Fenwick and Stocking were swept overboard and drowned. Stodder managed to hang on to the safety lines around the deck and cut through the hawser with a hatchet.

At 11 p.m. Bankhead sent the message to the Rhode Island, "Send your boats immediately, we are sinking!" Commander Stephen Decatur Trenchard called for the Rhode Island's engines to be stopped and her boats "away to the rescue!" The first boat, a launch, was commanded by Ensign A.O. Taylor. The second, a cutter, was commanded by Masters Mate Rodney Browne. Bankhead had the Monitor's engines stopped as well. Two boats from the Rhode Island reached the Monitor and Bankhead ordered Lt. Samuel D. Greene "to put as many men into them as they would safely carry."

Their power cut, the Monitor and the Rhode Island were drifting dangerously close together. One of the launches was caught between them and suffered damage, but remained afloat as sixteen men climbed in. The Rhode Island tried to pull away, but the hawser Stodder had cut had become entangled in the paddlewheel and was pulling the ships closer together. Sailors from the Rhode Island worked to cut the ships loose as they rolled heavily on the waves. Finally, the lines were freed and the Rhode Island began to drift away.

To get to the rescue boats, the men had to cross the rolling, storm-swept deck. Keeler described "Mountains of water ... rushing across our decks...the howling of the tempest, ... the bubbling cry of the strong swimmer in his agony and the whole panorama of horror which time can never efface from my memory." At midnight, Ensign William Rodgers launched the third boat from the Rhode Island. The distance between the two ships had increased considerably, and Browne's cutter was almost unmanageable. As it approached the Monitor, it collided with Taylor's overloaded launch trying to make its way to the Rhode Island. Surgeon Weeks, in the launch, reached out to the oncoming boat. The two boats scraped heavily as they passed, catching Weeks' right hand between the two, crushing three fingers and wrenching his arm "from its socket...."

Shortly after midnight, the water overcame the engine and the Monitor's pumps stopped, and with them, any hope of saving the ship. Bankhead reportedly said, "It is madness to remain here any longer ... let each man save himself." The boats from the Rhode Island were still coming to rescue the Monitor's half-drowned crew, but it was clear that not everyone would make it in one trip. Desperate men had to cling to the top of the turret until the lifeboats returned.

Browne's cutter arrived soon after Bankhead's call to abandon ship. He recalled, "We had now got in my boat all of the Monitor's crew that could be persuaded to come down from the turret for they had seen some of their shipmates who had left the turret for the deck washed overboard and sink in their sight." Many of the men who did leave the foundering ship threw shoes, clothing and possessions back into the turret so they would be able to swim if they needed to. Those same possessions were found by conservators and archaeologists following the recovery of the turret in August 2002.

Paymaster William Keeler later gave a moment-by-moment account of his escape from the Monitor: "...I divested myself of the greater portion of my clothing to afford me greater facilities for swimming... & attempted to descend the ladder leading down the outside of the turret, but found it full of men hesitating but desiring to make the perilous passage of the deck." Keeler's saga continued: "I found a rope hanging from one of the awning stanchions over my head & slid down it to the deck. A huge wave passed over me tearing me from my footing...I was carried ...ten or twelve yards from the vessel when ... the wave threw me against the vessel's side near one of the iron stanchions which supported the life line; this I grasped with all the energy of desperation & ...was hauled into the boat..."

John Bankhead returned to his cabin for his coat, and other small personal possessions. He took "one lingering look and ... left the Monitor's cabin forever." Master's Mate George Fredrickson returned a watch he had borrowed from another officer, saying, "Here, this is yours; I may be lost." Some of the men refused to leave—or simply couldn't. Francis Butts recalled that Engineer Samuel A. Lewis was too seasick to leave his berth.

On board the Rhode Island, Surgeon Samuel Gilbert Webber reset Weeks's arm and amputated parts of three fingers. Weeks came back to stand on deck with his Monitor shipmates, watching the sad drama unfold: "we watched from the deck of the Rhode Island the lonely light upon the Monitor's turret – a hundred times we thought it had gone forever, – a hundred times it reappeared, till at last...it sank and we saw it no more."

Browne and his men in the cutter were making "but slow progress" when the Monitor's light disappeared for good. Then, turning back to the Rhode Island, they were horrified to see her "...steaming away from us, throwing up rockets and burning blue lights – leaving us behind." Captain Trenchard searched for them all night and into the next day, when the search was abandoned and the Rhode Island steamed for Beaufort. Picked up by the schooner A. Colby the following day, Browne and his crew returned to the Rhode Island to be greeted by "hearty cheers."

Forty-seven men were rescued from the USS Monitor before she slipped beneath the waves. Sixteen were lost—either washed overboard while trying to reach the rescue boats or trapped inside the foundering vessel. Upon mustering the crew upon the Rhode Island, John Bankhead found the following men missing:

Landsman William Allen

Acting Ensign Norman Knox Attwater

Yeoman William Bryan

1st Class Boy Robert Cook

Landsman William H. Eagan

Quarter Gunner James R. Fenwick

Acting Ensign George Fredrickson

2nd Assistant Engineer Robinson Hands

| Officer's Cook Robert H. Howard

1st Class Fireman Thomas Joyce

3rd Assistant Engineer Samuel Augee Lewis

Coal Heaver George Littlefield

Landsman Daniel Moore

Seaman Jacob Nicklis

Boatswain's Mate Wells Wentz (aka John Stocking)

1st Class Fireman Robert Williams |

| |  | | |

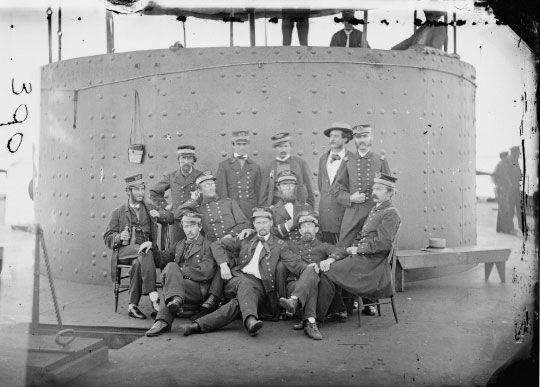

| | Gibson captured this image of the officers by the gun turret on July 9, 1862, while the Monitor was in the James River, Va. (Courtesy, National Archives)

Standing, top row, left to right:

Master's Mate George Frederickson;

Third Assistant Engineer Mark Trueman Sunstrom;

Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene;

Lieutenant L. Howard Newman (Executive Officer of USS Galena) and

First Assistant Engineer Isaac Newton.

Seated in chairs, middle row, left to right:

Acting Master Louis N. Stodder;

Acting Assistant Paymaster William F. Keeler;

Acting Volunteer Lieutenant William Flye; and

Acting Assistant Surgeon Daniel C. Logue.

Seated on deck in front, left to right:

Third Assistant Engineer Robinson W. Hands;

Second Assistant Engineer Albert B. Campbell; and

Acting Master E.V. Gager.

| |

For a more detailed account of the sinking of the Monitor, visit The Mariners' Museum website

| |

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html

indicates a link leaves the site. Please view our Link Disclaimer | Contact Us | http://monitor.noaa.gov/150th/includes/footer.html