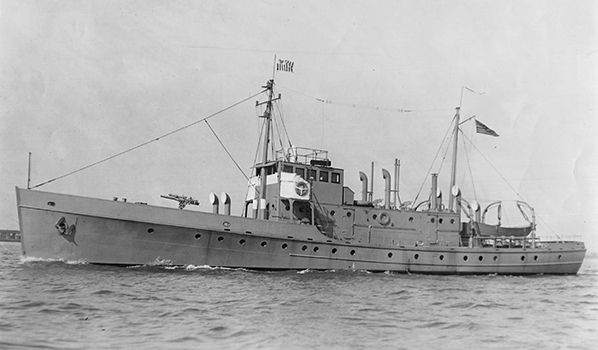

USCGC Jackson

Ship Stats

Depth: 77 feet

Vessel Type: U.S. Coast Guard Active Class Patrol Boat

Length: 125 feet Breadth: 23 feet 6 inches

Gross Tonnage: 232 tons Cargo: N/A

Built: American Brown Boveri Electric Company, Camden, New Jersey, and commissioned on

March 14, 1927

Hull Number: Unknown Port of Registry: Morehead City, North Carolina, USA

Owner: U.S. Coast Guard

Former Names: None

Date Lost: September 14, 1944

Sunk By: Great Atlantic Hurricane Survivors: 20 of 41 (21 dead)

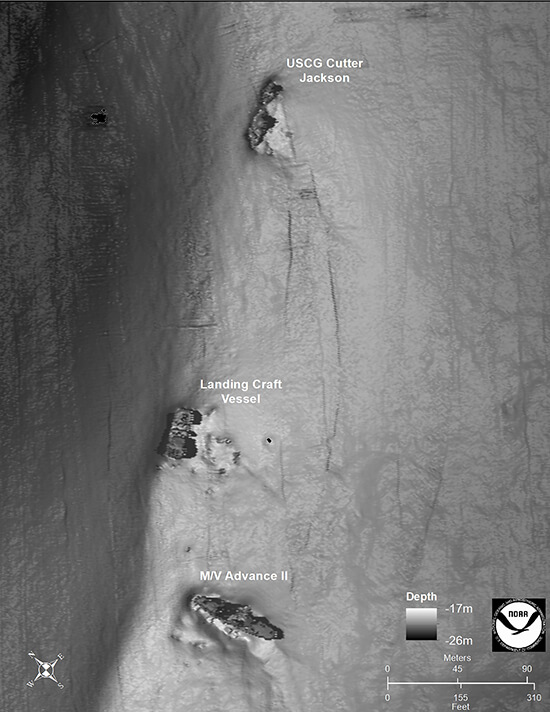

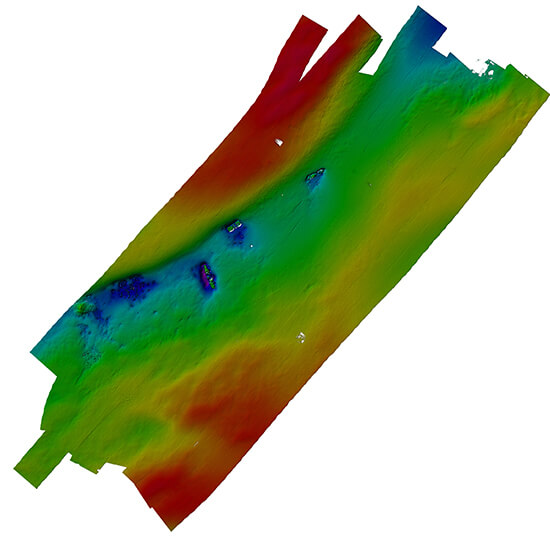

Data Collected on Site: High resolution multibeam sonar images

Significance: Served during World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic as a submarine chaser and patrol vessel. It sank in what became known as the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944 with the loss of 21 sailors.

Wreck Site

The USCGC Jackson rests in 77 feet of water just southeast of Nags Head, North Carolina. Typical visibility at the wreck site ranges from 15 to 25 feet, but on exceptional days, it can range up to 30 to 40 feet. The ship is broken in two sections, bow and stern, with a 20-foot gap between the sections. The port bow rises up from the seafloor, and Jackson’s anchor remains in the hawse pipe. The starboard side of the bow lays in the sand, and just aft of the bow section is a deck gun, also lying in the sand. In the gap between the two sections, a steering quadrant is visible. The stern section sits upright with a large debris field scattered across the surrounding sandy seafloor. In recent years, more of the stern has been uncovered, and a majority of the starboard stern area is now exposed.

Historical Background

USCGC Jackson was built in 1926 at the American Brown Boveri Electric Company in Camden, New Jersey, and commissioned into the U.S. Coast Guard on March 14, 1927. Based out of USCG Station Boston, the cutter joined the efforts to combat smugglers and bootleggers off the East Coast. At the end of Prohibition, the cutter was reassigned to the Great Lakes and began operations out of the U.S. Coast Guard Station Rochester. There, it participated in traditional Coast Guard missions of search and rescue, fisheries patrols, and maritime law enforcement.

As World War II worsened in Europe, USCGC Jackson was reassigned as part of the effort to strengthen U.S. armed forces along the East Coast. Following the United States’ entry into World War II, USCGC Jackson was placed into operational control of the U.S. Navy and assigned to the Eastern Sea Frontier (EASTSEAFRON). Over the next two years, Jackson and its crew had the dangerous duty of convoy escort and antisubmarine patrols along the Eastern Seaboard. While providing protection to ships transiting, Jackson also rescued shipwrecked sailors, assisted damaged and disabled ships, and hunted enemy submarines into the summer of 1944.

On September 14, 1944, USCGC Jackson was stationed at Morehead City, North Carolina, when it was ordered to join its sister ship USCGC Bedloe to assist the torpedoed Liberty Ship SS George Ade, which was under tow by the U.S. Navy Tug Escape (ATR-6) off Cape Hatteras. As they began escorting the George Ade, both cutters encountered rapidly-deteriorating weather conditions and mounting seas as the Great Atlantic Hurricane made its presence known. The storm would reach its peak strength just south of North Carolina.

Steaming off the Outer Banks, cutters Jackson and Bedloe received several storm warnings. At dawn that Thursday, seas reached as high as 50 feet and winds blew over 50 miles per hour. Jackson’s crew battened down the hatches and disarmed the depth charges. By 9:00 a.m., conditions became terrifying with driving rains and seas so high the cutter’s radar failed to locate any radar contacts hidden behind the towering waves.

As wave heights increased to between 50 and 100 feet, riding the cutter resembled an amusement park ride with the sea lifting the cutter onto the crest of the wave and then plunging the ship into the void on the other side. By 10:00 a.m., winds were believed to be over 100 miles per hour. Huge waves that eyewitnesses believed to be 100 feet high, forced Jackson down their faces only to slam the ship into a wall of water at the base of the next monster wave. The worsening conditions made many of the crew wonder if they would survive.

Late in the morning, a series of larger waves, likely mountains of water referred to as rogue waves, hit Jackson. The first wave carried Jackson to its crest, but the ship recovered. Then a second towering wave rolled the ship on its port side, forcing the mast into the sea. A third wave, described by a crewmember as “a pyramid with a huge curl on top” and estimated as high as 125 feet, bore Jackson on its crest where survivors said the ship hung in mid-air for seconds. There, the hurricane’s blasting winds blew the cutter on its side, and it plummeted from the wave top to the bottom of the trough 100 feet below. This time, Jackson failed to right itself, filled with water, and disappeared into the hole between the colossal waves.

Most but not all of the crew escaped the capsized cutter. Only a few were trapped in its darkened compartments or fell into the roiling water. However, several who made their way outside had no life preservers in a fury of gigantic waves and 125-mile-an-hour winds. Of those who managed to get to a raft, the seas ripped them from the raft every time it flipped over. Each time the raft righted itself, fewer men had the strength to climb back aboard.

After the storm subsided, the remaining men floated for two more days. Exhaustion and exposure took their toll on the remaining survivors. Of the 41 men aboard Jackson, 37 men got into Jackson’s rafts, but over the course of 58 hours, only 20 survived. These cuttermen were not old timers—they were young men in their physical prime, with most of the officers and enlisted men in their late teens and twenties, including Jackson’s skipper, who was only 23 years old. The survivors were picked up by a crew from the Oregon Inlet Lifeboat Station.

The Jackson fought the good fight and lost against the most formidable and deadly waves found in the world’s ocean. Jackson and its brave crew, and the men of the Bedloe, will be remembered as part of the Service’s long blue line.